World-famous constructed languages range from Zamenhof’s Esperanto to Tolkien’s Quenya to hobbyist “conlangs”, but isn’t it surprising to learn that centuries before them, an Ottoman in Egypt created his own language and that a thorough grammar and lexicon survives to this day?

Conlanging before it became cool was the scholar and mystic Mehmed ibn Fethullah ibn Ebü Tâlib, born in Edirne in the mid-16th century and spending the majority of his life in Ottoman Cairo.

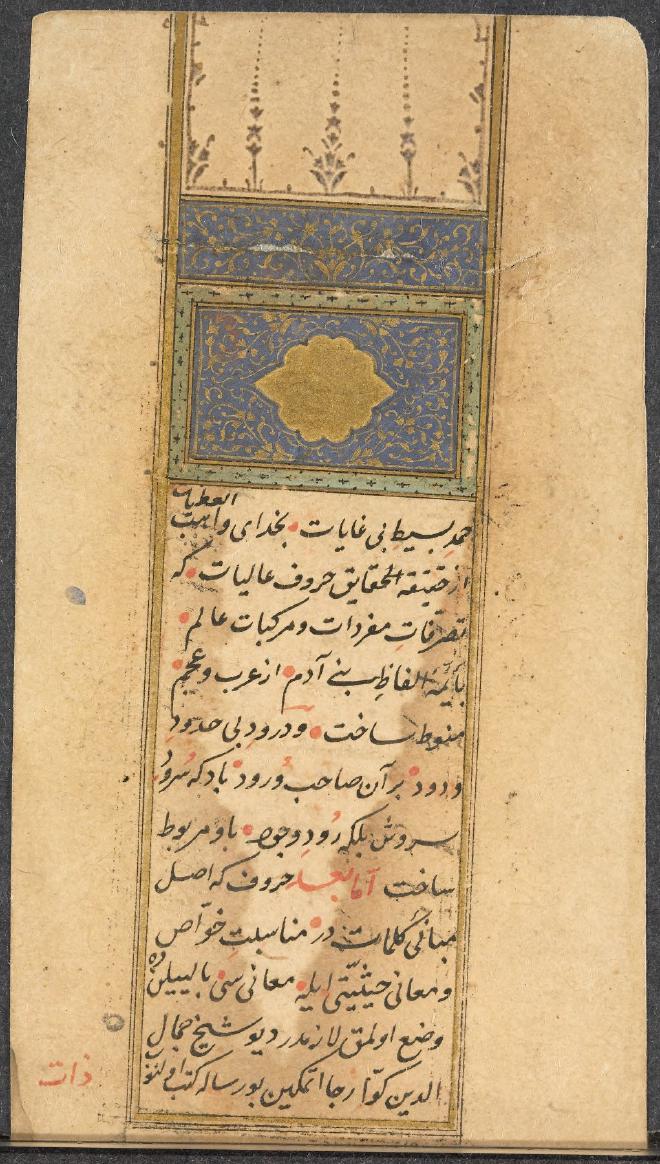

I started writing an English-language overview of Bāla’y-balan’s grammar based on both the original text as preserved in Princeton University’s library and a modern Turkish translation by Mustafa Koç, Bâleybelen. Muhyî-i Gülşenî. İlk Yapma Dil.

The “full” PDF is available for download, but here are a few short excerpts:

Words in Bāla’y-balan are not required to have vowel harmony, a distinguishing feature of the Turkish language. Words such as qaydak kapı ‘door, gate’, which has both a back q and a front k, would not be possible in a pure Turkish word. This point has further significance when we consider Bāla’y-balan’s suffixes, which will not harmonise with the vowels in the root to which they are attached.

The Bāla’y-balan plural is created by the addition of the suffix -ā: نو niv ‘flower’ and نوا nivā ‘flowers’. When the base noun already ends with a -ā, then -y- is added as a buffer between the two vowels. When the base noun ends in the vowel ه [a], then the long ā is added, and the ه is vocalised with its consonontal value [h]: ظفه ẓafa ‘book’, ظفها ẓafahā.

A noun may be placed in accusative case by the addition of the suffix -rā. This may be added to both singular and plural nouns: شَمْسَا نِوَارَا Şamsā nivārā ‘They smelled the flowers’.

Download